On the edge of a great forest there lived a poor woodcutter with wife and his two children; the little boy was called Hansel and the girl Gretel. He had little enough to put in his belly, and once, when a great famine came upon the land, he could not even provide their daily bread. As he lay in bed one evening, brooding over this and tossing and turning with worry, he sighed and said to his wife: "What's to become of us? How can we feed our poor children when we've nothing left for ourselves?" "Do you know what, husband?" answered his wife. "Tomorrow morning, very early, let us take the two children out into the forest where it is thickest. There we'll light them a fire and give each of them an extra piece of bread, then we'll go off to our work and leave them on their own. They won't find their way back home, and we'll be rid of them. "No, wife," said the man, "that I won't do; how could I have the heart to leave my children alone in the forest; it wouldn't be long before the wild beasts came and tore them to shreds." "Oh, you fool," she said, "then we're bound to die of hunger, all four of us; you can just plane the boards for the coffins." And she gave him no peace until he complied. "But I'm sorry for the children, all the same," the husband said.

The two children had not been able to sleep for hunger either, and they had heard what their stepmother had said to their father. Gretel wept bitterly and said to Hansel: "Now it's all up with us." "Hush, Gretel," said Hansel, "don't fret, I'll get us out of this." And when the grown-ups had fallen asleep, he got up, put on his jacket, opened the door downstairs, and slipped out. The moon was shining clear, and the white pebbles in front of the house were glistening as bright as pennies. Hansel stooped down and crammed his little pocket with as many as could fill them. Then he went back and said to Gretel: "Don't worry, sister dear, go to sleep peacefully. God won't forsake us," and lay down on his bed.

At daybreak, even before the sun had risen, the woman came and woke the two children. "Get up, you pair of lazybones, we want to go into the forest to fetch wood." Then she gave them each a little piece of bread, saying: "Here's something for midday. But mind you don't eat it before then, because you're not getting any more." Gretel took the bread beneath her apron, because Hansel had the stones in his pocket. Then they all made their way together towards the forest. After they had been walking for a little while Hansel stopped and looked back towards the house, and he did so over and over again. His father said: "Hansel, what are you looking back at? Why are you dawdling all the time? Watch out, my boy, and mind where you're going." "Oh, father," said Hansel, "I'm looking back at my little white cat; she's sitting up on the roof and wants to say goodbye." The woman said: "Little fool, that's not your cat; that's the morning sun shining on the chimney." But Hansel hadn't been looking back at the cat; instead, each time he had dropped one of the bright pebbles from his pocket.

When they had come to the middle of the forest their father said: "Now, go and gather some wood, children. I'll light a fire so that you don't get frozen." Hansel and Gretel gathered up brushwood, a little mountain of it. The brushwood was lit, and when the flames rose high the woman said: "Now lie down by the fire, children, and have a rest. We're going into the forest to cut wood. When we're finished we'll come back and fetch you."

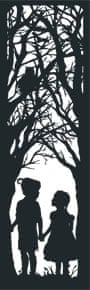

Hansel and Gretel sat by the fire, and when midday came they each ate their piece of bread. And because they heard the blows from the woodman's axe, they thought their father was nearby. But it wasn't the woodman's axe; it was a bough he had tied to a dead tree, blowing to and fro in the wind. And as they had been sitting for such a long time, their eyes closed with weariness and they fell fast asleep. At last, when they woke, darkest night had fallen. Gretel began to cry, and said: "How are we to get out of the forest now?" But Hansel comforted her: "Just wait a little while until the moon has risen, and then we'll find our way, that's for sure." And when the full moon had risen Hansel took his little sister by the hand and followed the pebbles, which were shining like new-minted pennies and showed them the way. They walked all through the night, and as day was dawning they arrived at their father's house. They knocked at the door, and when the wife opened it and saw that it was Hansel and Gretel, she said: "You bad children, falling asleep for so long in the forest like that. We thought you would never come back." But their father was glad, for it had cut him to the quick that he had left them so dreadfully alone.

Not long afterwards there came another time of hardship everywhere and the children heard what their mother was saying to their father in bed at night: "The cupboard is empty again; all we have left is half a loaf of bread. After that, it's all finished. We have to get rid of the children. We'll take them deeper into the forest, so that they won't be able to find their way out; there's no saving us otherwise." At this the man's heart grew heavy, and he thought: it would be better if you shared your last bite with the children. But the woman would not listen to anything he said, and scolded and berated him. If you take the first step, you must take the next, and because he had given in the first time he was bound to do so the second time as well.

But the children were still awake, and they had listened in to this conversation. When the grown-ups were asleep Hansel got up again and tried to go out and gather pebbles. But the woman had locked the door and Hansel could not get out. But he comforted his little sister, saying: "Don't cry, Gretel, go to sleep quietly, the good Lord will help us."

Early next morning the woman came and fetched the children from bed. They were given their bit of bread, but it was even smaller than the last time. On the way to the forest Hansel crumbled it up in his pocket, and kept stopping to drop a crumb on to the ground. "Hansel, why are you standing and looking round?" his father said. "Get on your way." "I'm looking back at my little dove. She's sitting on the roof and wants to say goodbye," answered Hansel. "Little fool," said the woman, "that's not your dove; that's the morning sun shining on the chimney." But bit by bit Hansel dropped the crumbs along their path.

The woman led the children still deeper into the forest, where they had never been before in their lives. Once again a big fire was lit, and their mother said: "You children, just stay and sit there, and if you're tired you can sleep a while. We're going into the forest to cut wood, and in the evening, when we're finished, we'll come and fetch you." When it was midday Gretel shared her bread with Hansel, for he had scattered his piece along the way. Then they fell asleep. Evening came and went, but no one came to fetch the poor children. They did not wake until it was dark night, and Hansel comforted his little sister and said: "Just wait, Gretel, until the moon rises, and then we'll see the crumbs of bread I scattered. They'll show us the way home." When the moon rose they got up, but they didn't find any crumbs, for the thousands and thousands of birds who fly about in forest and field had pecked them all up. Hansel said to Gretel: "We'll surely find our way." But they didn't. They walked the whole night long and the next day from morning to evening, but they couldn't get out of the forest, and they were so hungry, for they had eaten nothing but the few berries they had found lying on the ground. And because they were so weary that their legs could no longer carry them, they lay down beneath a tree and fell asleep.

And now three days had passed since they had left their father's house. They began walking again, but only went deeper and deeper into the forest, and if help didn't come soon they were bound to die of hunger. When midday came they saw a lovely snow-white bird sitting on a bough and singing so beautifully that they stopped to listen. And when it had finished it spread its wings and flew ahead of them, and they followed it until they came to a little house, where it perched on the roof, and when they came quite close they saw that the house was made of bread and the roof was made of cake; as for the windows, they were made of pure sugar. "Let's fall to," said Hansel, "and say grace for such a meal. I'll eat a bit from the roof, and Gretel, you can eat some of the window, that'll taste sweet." Hansel reached up and broke off a little of the roof to eat, to see what it tasted like, and Gretel stood by the window panes and nibbled at them. Then a little voice called out from the parlour:

"Nibbledydee, nibbledyday,

Who's nibbling at my house today?"

The children were answered:

"The wind, the wind,

The heavenly friend"

And they went on eating unconcernedly. Hansel, who was really enjoying the roof, tore down a big piece, and Gretel pushed out a whole round window pane, sat down, and ate it up with pleasure. Then all at once the door opened and an ancient woman, leaning on a crutch, came creeping out. Hansel and Gretel were so dreadfully frightened that they dropped what they were holding in their hands. But the old woman shook her head and said: "Well, well, children dear, who's brought you here? Come right in and stay with me. You won't come to any harm." She took them both by the hand and led them into her little house. There was good food on the table, milk and pancakes with sugar, and apples and nuts. Afterwards there were two lovely little beds with white sheets, and Hansel and Gretel lay down in them and thought they were in heaven.

The old woman had only pretended to be so kind; she was really a wicked witch who lay in wait for children, and she had only built the little bread house to lure them to her. If one of them fell into her clutches she would kill him, cook him, and eat him, and to her that was a proper feast day. Witches have bloodshot eyes and they can't see very far, but they have a very fine sense of smell, like the animals, and they can tell when human children come their way. When Hansel and Gretel drew near her, she laughed spitefully and said, gloating: "I've got them. They shan't escape me again." Early next morning, before the children had woken, she was already up, and when she saw the two of them resting there so sweetly, she muttered to herself: "That'll make a good mouthful." Then she grabbed Hansel with her skinny hand and carried him off into a little pen and locked him up behind the bars; shout as he might, it was no good. Then she went up to Gretel, shook her awake, and cried: "Get up, you lazybones, fetch water and cook something tasty for your brother. He's locked in the pen outside and has to be fattened up. When he's nice and fat, I'll eat him." Gretel began to cry bitterly but it was no use; she had to do what the wicked witch commanded.

Now poor Hansel had the very best meals cooked for him, but Gretel got nothing but the shells from the crayfish. Every morning the old woman stole to the little stable and called: "Hansel, stick out your finger, so that I can feel how soon you'll be fattened." But Hansel stuck a little bone out for her, and the old woman, whose eyes were dim, could not see it and thought it was Hansel's finger, and she was puzzled that he wasn't fattening up at all. When four weeks had gone by and Hansel still remained bony, she was overcome by impatience and wouldn't wait any longer. "Hey, Gretel," she called to the girl, "look sharp and bring water: fat or lean, tomorrow I'll slaughter Hansel and stew him." Oh, how his poor little sister wailed as she had to fetch the water, and how the tears poured down her cheeks! "Dear Lord, please help us," she cried. "If only the wild beasts had eaten us, we would at least have died together." "Save your moaning," said the old woman, "it won't do you any good."

Early next morning, Gretel had to go out, hang up the cauldron full of water, and light the fire. "We'll do the baking first," said the old woman. "I've already fired the oven and kneaded the dough." She shoved poor Gretel out to the baking-oven, from which the flames were already blazing. "Crawl inside," said the witch, "and see whether it is the right heat, so that we can push in the bread." Once she had Gretel inside she was going to shut the oven door, and Gretel would roast in there and she would eat her up as well. But Gretel saw what she had in mind and said: "I don't know how to do it. How do I get inside?" "Stupid goose," said the old woman, "the opening is big enough. As you can see, I can get in myself." And she hopped towards Gretel and stuck her head in the oven. Then Gretel gave her a shove so that she was pushed far inside, shut the iron door fast, and fastened the bolt. Oh, then she began to howl, enough to make your flesh creep; but Gretel ran off, and the godless witch burned miserably to death.

Gretel, though, ran straight off to Hansel, opened his little pen, and called: "Hansel, we're saved; the old witch is dead." Then Hansel leapt out like a bird from a cage when its door is opened. How glad they were, they hugged each other, and skipped about and kissed! And because they need be afraid no longer they went into the witch's house, and in every corner there stood chests full of pearls and precious stones. "These are even better than pebbles," said Hansel, and stuffed his pockets with as much as they could hold; and Gretel said: "I'll take something home with me too, and filled her apron full. "But let's go away now," said Hansel, "so that we get out of the witch's forest." After they had been walking for a few hours they came to a great stretch of water. We can't get across," said Hansel, "I can't see a footway, nor a bridge." "There isn't a boat here, either," said Gretel, "but there's a white duck swimming. If I ask her, she'll help us to get over." Then she called:

"Little duck, little duck,

Here are Gretel and Hansel.

No bridge and no track,

Let us ride on your white back."

And the little duck really did swim up to them. Hansel sat on her back and told his sister to sit by him. "No," answered Gretel, "it will be too heavy for the little duck. She can carry us over one by one."

The good little creature did so, and when they were over without mishap and had been walking for a little while, the forest seemed to them to become more and more familiar, and at last from afar they could see their father's house. Then they began to run, burst into the parlour, and flung their arms about their father's neck. The man had not had a glad hour since he had abandoned the children in the forest; as for his wife, she had died. Gretel shook out her little apron so that the pearls and precious stones leapt about in the parlour, and Hansel threw one handful after another from his pockets as well.

Then all their cares were at an end and they lived in sheer joy together. My story's done. See a mouse run. And whoever catches it can make a great big furry hood from it.